Compassion with a Long View: COVID and the Brain 🧠

Issue 8 is all about what Covid does to our beautiful brains (and a little surprise!)

Hi, friends! Welcome to The Lovely Brains Newsletter, where I write about my experience with brain injury. I write on the first of every month and share what I’m working on and thinking about. Thanks for being here! As far as this post goes, I’m not a doctor and am only speaking from my experience, so please consult reliable medical providers for your health.

Oh, mono

My experience with post-viral illness started at the beginning of my junior year of high school when I was diagnosed with mono. Instead of getting sick for a few weeks and then recovering, I continued to feel drained of vitality. In the morning, I would wake up feeling like I hadn’t slept at all. My brain was under a heavy fog. I remember trying to simply focus on my chemistry homework as I lay prone in bed just barely being able to keep my eyes open.

The fatigue persisted so intensely that I had to quit the tennis team, which was one of my favorite extracurriculars. I was poised to break onto the varsity squad, but I needed to conserve my limited energy for schoolwork. When I returned to the team my senior year, I wasn’t the same player. I could barely function at the bottom of junior varsity. Standing on the court and swinging my racket was so effortful. I became winded easily. My physical energy didn’t recover to near–pre-injury levels until my junior year in college, five years later.

Other than visiting my primary care doctor for blood work to confirm I had mono, I essentially had no medical help and didn’t realize I could or should keep searching for answers and solutions. I rode it out, while the virus ran amok. My body eventually rallied. Emotionally, it was tough to have degrees of my energy siphoned away, to be unable to use my body’s stamina to its full potential. I wonder if the post-viral fallout from that infection contributed to the intensifying anxiety and depression I experienced in college. It wasn’t until my last brain injury that I realized just how wild that experience was and how much I needed medical interventions to help me heal.

Traumatic Brain Injury and COVID

The fatigue I experienced after my brain injury was even more intense than the fatigue I experienced with mono. It seems likely to me that the brain injury reactivated whatever underlying virus caused the mono. This previous encounter with a virus added another layer to sort through. I think it’s possible I had COVID in February 2020, and I have had lingering post-viral symptoms from that illness that have lasted much of the pandemic, shape-shifting and resurging. For me, the post-viral fallout has been mild because I think I had some built-in immunity from a coronavirus infection in 2018, the one that had me in bed and coughing for four months and that left me with a rasp in my left lung.

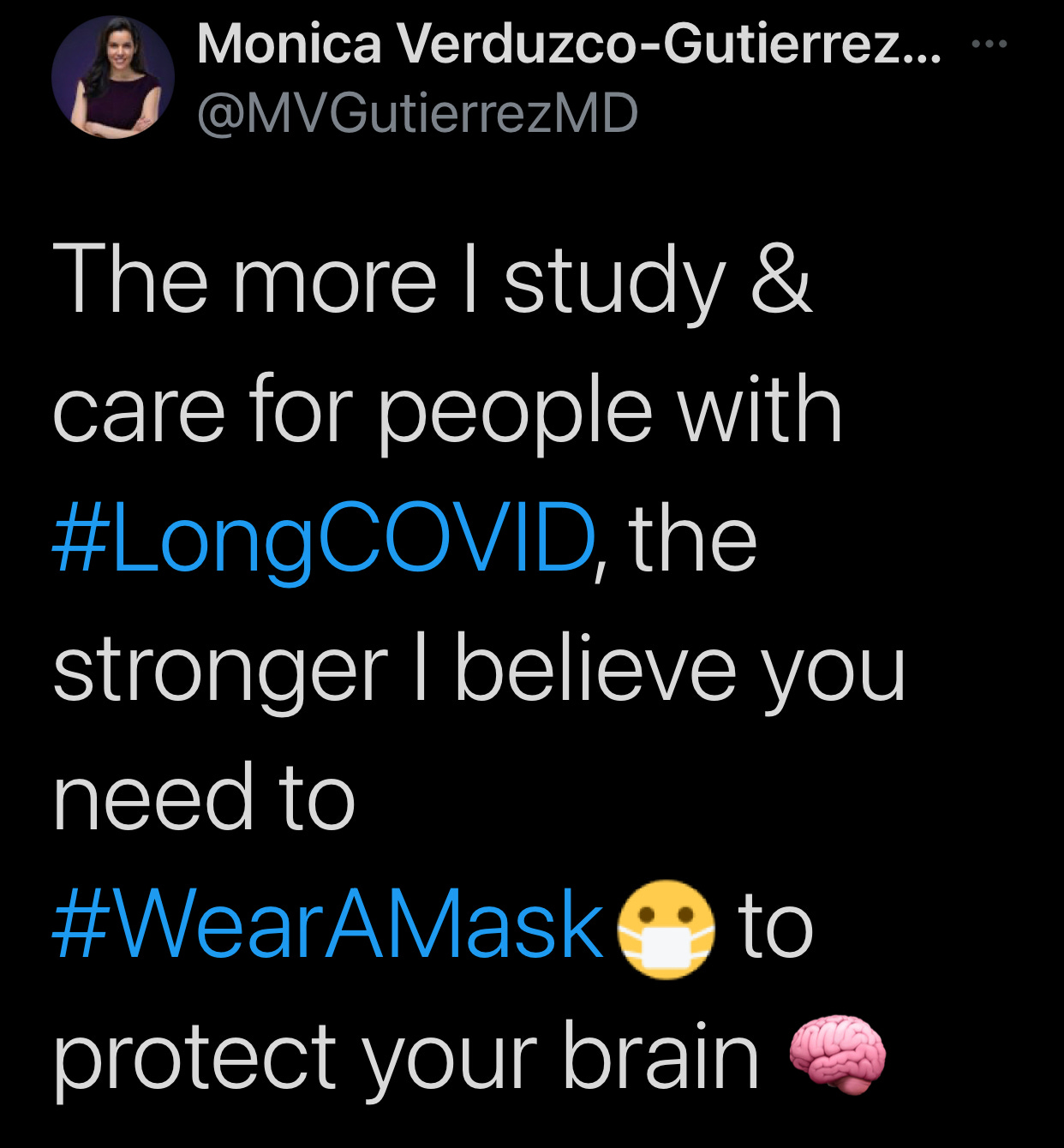

When COVID burst on the scene, because of these previous experiences and the research coming out about the virus, I was committed to extreme caution. Persistent cognitive symptoms were appearing in patients and brain damage was visible in those who had died. The virus was affecting patients’ central nervous systems. I knew that I did not want the virus, that I did not want *anyone* to have the virus. Based on stories of long-COVID, I was devastated that this could become a long-term illness and disability for which people would be misdiagnosed and disbelieved. The recovery process for them might be grueling and expensive.

For many, their encounter with COVID is incredibly devastating. Reading Hannah Davis’s list of long-COVID symptom presentations (cited below) is eye opening. Although I couldn’t relate to all the symptoms, I knew what it was like to have dysautonomia, nerve problems, brain stem and vagus nerve issues, metabolic and blood flow changes in the brain, and immune injury. I know what it’s like to do your own medical research constantly while your brain and body are in state of agonizing collapse. I know what it’s like to be dependent on others for daily help. What these survivors experience is extremely serious.

A viral brain injury is still a brain injury. People don’t like to talk about or think about brain injuries. If they’ve never had one, or if they don’t recognize that they’ve had one, they don’t know what it means to have multi-system impacts descend furiously all at once, a biological enigma that when improperly treated becomes a waking nightmare of persistent symptoms.

Compassion with a long view

We don’t know what the long-term nervous system outcomes of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 will be. It already doesn’t look good. The New York Times just reported on a Lancet study that found half of COVID patients have a lingering symptom a year later, and that brain health issues like anxiety and depression are actually worse at the year mark compared to the 6-month mark of illness. “There is an ongoing discussion whether COVID-19 may cause long-term cognitive impairments. Such a theory is supported by several studies showing a link between infections with human herpes viruses and the risk of dementia development later in life. Neurodegeneration could possibly emerge many years after viral infections in the CNS” (Cognitive Impairment After COVID-19—A Review on Objective Test Data). The same people who refuse to wear masks may experience viral reactivation later in their lives and struggle with their cognitive performance as they age.

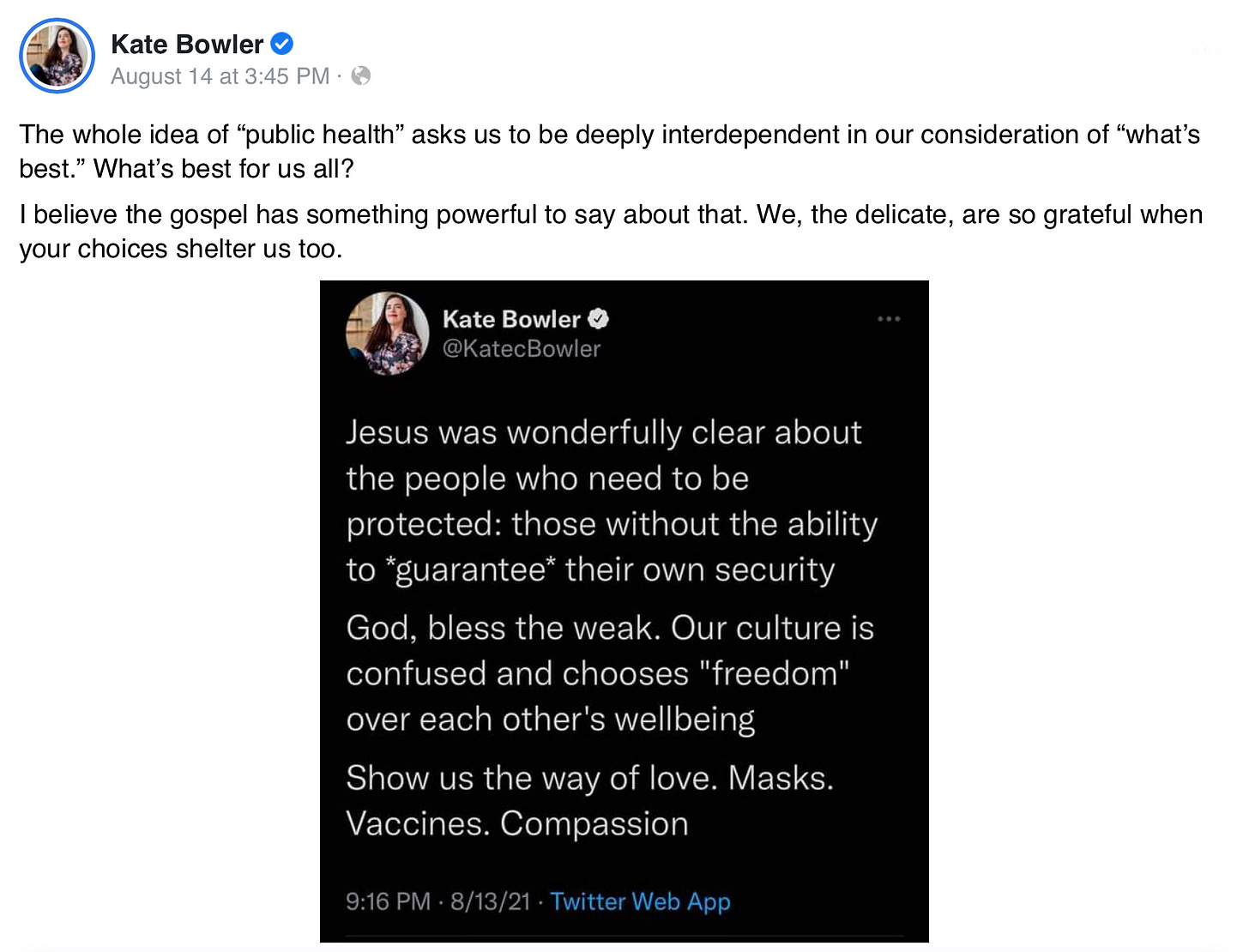

Refusing to wear masks because someone wants freedom is simply a lack of foresight and a misunderstanding about what viruses can do in the body now and over the long-term. It also displays dangerous unkindness to one’s vulnerable neighbors (that’s potentially all of us!). We need compassion with a long view, where we collectively commit to doing no harm to each other. Preventing people from being infected with a highly transmissible and preventable illness is an individual and societal Good.

The brain can and does heal. We are in an amazing age of brain healing, but we are only as well as the weakest among us. Any of us can become the vulnerable at any time through injury or accident or natural disaster, reliant on the kindness of strangers. Let’s be kind strangers to all those we’ll never meet.

I created a journal!

In last month’s newsletter I announced that I was creating a planner to help people manage their brain rest throughout the day. That’s still coming. But it’s taken a bit of a back seat for now. In the process of creating that planner, I found another journal that I wanted to create first while I continue to research and plan the other. This one is called The Gentle Prayer Journal: 60 Days of Drawing Closer to God.

My poetry and art book The Brain’s Lectionary: Psalms and Observations contains some of the prayers and psalms I wrote while recovering from my injury. Prayer has been an ongoing difficulty for a long time, but especially after my injury. I haven’t had a journal where I organize or give those thoughts life. I figure, if a journal like this is a need for me, it probably is for other people, too.

I’m hoping to have this journal finished when the book comes out, so that people have a practical prayer tool for when they’re going through a hard time (which, is pretty much everybody right now, right?).

If you’d like to beta test the journal, head to my website. You’ll be prompted to download a week’s worth of pages, and you’ll take a Google survey after you use them. Once you do that, you’ll be entered in a drawing to win a copy of the planner when it comes out!

Thanks for your help in advance, and thanks for being a community of trusted readers and friends!

Want to read about how COVID affects the brain? Here are some articles I found.

Disclaimer: I haven’t made it through them all in their entirety, but they look reputable.

Beyond the Symptom: The Biology of Fatigue | Sponsored by the National Institutes of Health Blueprint for Neuroscience Research and in collaboration with the

Sleep Research Society (September 27-28, 2021)

Register for free at the link above. Of particular interest are Session 2 “Theories for Mechanisms of Fatigue,” “Neuron-glia Metabolic Coupling: Roles in Plasticity and Pathology,” “Gut-brain Axis,” “Reactive Oxygen Species in the Brain and in the Periphery,” and “Session 4, Neurobiology of Fatigue.”

Acute and chronic neurological disorders in COVID-19: potential mechanisms of disease | Brain, Oxford University Press (August 16, 2021)

Abstract. COVID-19 is a global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection and is associated with both acute and chronic disorders affecting the nervous system. Acute neurological disorders affecting patients with COVID-19 range widely from anosmia, stroke, encephalopathy/encephalitis, and seizures to Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Chronic neurological sequelae are less well defined although exercise intolerance, dysautonomia, pain, as well as neurocognitive and psychiatric dysfunctions are commonly reported. Molecular analyses of cerebrospinal fluid and neuropathological studies highlight both vascular and immunologic perturbations. Low levels of viral RNA have been detected in the brains of few acutely ill individuals. Potential pathogenic mechanisms in the acute phase include coagulopathies with associated cerebral hypoxic-ischemic injury, blood-brain barrier abnormalities with endotheliopathy and possibly viral neuroinvasion accompanied by neuro-immune responses. Established diagnostic tools are limited by a lack of clearly defined COVID-19 specific neurological syndromes. Future interventions will require delineation of specific neurological syndromes, diagnostic algorithm development, and uncovering the underlying disease mechanisms that will guide effective therapies.

Ryan O'Hare, Problems in thinking and attention linked to COVID-19 infection | Imperial College London (August 12, 2021)

Hannah Davis, “When it comes to breakthrough cases, are we ignoring long Covid once again?” | The Guardian (August 12, 2021)

We know much more about long Covid than we did this time last year – enough for us to know it’s severe. Research has found ongoing endothelial dysfunction, hypometabolism in the brains of long Covid patients, microclots in long Covid blood samples, reduced aerobic capacity and impaired systemic oxygen extraction in non-hospitalized patients without cardiopulmonary disease, disrupted gut microbiota that persists over time, damage to corneal nerves, immunologic dysfunction persisting for at least eight months, numerousfindings of dysautonomia (a common post-viral disorder of the autonomic nervous system), and countless other conditions.

In a cohort of non-hospitalized patients, 31% were dependent on others for care; our own paper from the Patient-Led Research Collaborative found over 200 multi-systemic symptoms that impaired the ability to work and function in daily life. We also found high levels of cognitive dysfunction and memory loss that were as common in 18-29-year-olds as those over 70, a finding that is starting to be highlighted in children and teenagers as well.

The mechanisms for the pathophysiology behind long Covid are complex; one comprehensive paper suggested “consequences from acute Sars-CoV-2 injury to one or multiple organs, persistent reservoirs of Sars-CoV-2 in certain tissues, re-activation of neurotrophic pathogens such as herpesviruses under conditions of Covid-19 immune dysregulation, Sars-CoV-2 interactions with host microbiome/virome communities, clotting/coagulation issues, dysfunctional brainstem/vagus nerve signaling, ongoing activity of primed immune cells, and autoimmunity due to molecular mimicry between pathogen and host proteins” as a few of the many possibilities. This type of complex research will take years to undertake and uncover, leaving patients suffering without treatment.

And all of this does not include the eventual “long” long-term findings that may be revealed in the decades to come. Recent studies show cognitive decline even in truly mild recovered patients; some doctors are worried about the possibility of a future wave of dementia or Alzheimer’s patients, a theme echoed at a recent NIH conference on neuropsychiatric effects of Covid.

Trevor Kilpatrick, Steven Petrou, How does COVID affect the brain? Two neuroscientists explain | The Conversation (August 10, 2021)

Fight-or-Flight Response Is Altered in Healthy Young People Who Had COVID-19 | Journal of Psychology(August 9, 2021)

New research published in the Journal of Physiology found that otherwise healthy young people diagnosed with COVID-19, regardless of their symptom severity, have problems with their nervous system when compared with healthy control subjects. Specifically, the system that oversees the fight-or-flight response, the sympathetic nervous system, seems to be abnormal (overactive in some instances and underactive in others) in those recently diagnosed with COVID-19.

Pam Belluck, ‘This Is Really Scary’: Kids Struggle With Long Covid | New York Times (August 8, 2021)

Will, an Eagle Scout, a talented tennis player and a highly motivated student who loves studying languages so much that he takes both French and Arabic, said he used to feel “taking naps is a waste of sunlight.”

But Covid made him so fatigued that he could barely leave his bed for 35 days, and he was so dizzy that he had to sit to keep from fainting in the shower. When he returned to his Dallas high school classes, brain fog caused him to see “numbers floating off the page” in math, to forget to turn in a history paper on Japanese Samurai he’d written days earlier and to insert fragments of French into an English assignment.

“I handed it to my teacher, and she was like ‘Will, is this your scratch notes?’” said Will, adding that he worried: “Am I going to be able to be a good student ever again? Because this is really scary.”

Emily DeCiccio, “New Covid study hints at long-term loss of brain tissue, Dr. Scott Gottlieb warns” | NBC News (July 17, 2021)

“The diminishment in the amount of cortical tissue happened to be in regions of the brain that are close to the places that are responsible for smell,” he said. “What it suggests is that, the smell, the loss of smell, is just an effect of a more primary process that’s underway, and that process is actually shrinking of cortical tissue.”

Michael Marshall, COVID and the brain: researchers zero in on how damage occurs | Nature (July 7, 2021)

Robert Stevens, MD, How Does Coronavirus Affect the Brain? | Johns Hopkins Medicine (June 4, 2021)

Patients with COVID-19 are experiencing an array of effects on the brain, ranging in severity from confusion to loss of smell and taste to life-threatening strokes. Younger patients in their 30s and 40s are suffering possibly life-changing neurological issues due to strokes. Although researchers don’t have answers yet as to why the brain may be harmed, they have several theories.

Mary Van Beusekom, COVID-19 damages brain without infecting it, study suggests | Center for Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota (April 19, 2021)

Carl Sherman, The Brain and Covid: Strides and Speculations | Dana Foundation (April 15, 2021)

Andrew E. Budson, MD, The hidden long-term cognitive effects of COVID-19 | Harvard Health Blog (March 4, 2021; originally October 8, 2020)

There is one inevitable conclusion from these studies: COVID infection frequently leads to brain damage — particularly in those over 70. While sometimes the brain damage is obvious and leads to major cognitive impairment, more frequently the damage is mild, leading to difficulties with sustained attention.

Although many people who have recovered from COVID can resume their daily lives without difficulty — even if they have some deficits in attention — there are a number of people who may experience difficulty now or later. One recently published paper from a group of German and American doctors concluded that the combination of direct effects of the virus, systemic inflammation, strokes, and damage to bodily organs (like lungs and liver) could even make COVID survivors at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease in the future. Individuals whose professions involve medical care, legal advice, financial planning, or leadership — including political leaders — may need to be carefully evaluated with formal neuropsychological testing, including measures of sustained attention, to assure that their cognition has not been compromised.

Megan Brooks, More Proof COVID Severely Affects the Brain | WebMD

See you next month! Thanks for reading and if you want to support this newsletter, please consider subscribing, or share this post with a brain injury survivor or advocate!